It is hard now to imagine when telling the time was a difficult thing to do. With everyone having a phone or at least a watch, it is easy to forget that not that long ago public time pieces were, for many, the best available option for getting to work on time, making sure they caught the train or made the meeting.

It’s amazing how many of these clocks and timepieces were sited around Sydney, and even more amazing how many survive still. The most prominent of these were the clock towers, which in their day, loomed over the low scale city round them and were visible to all the workers scurrying back and forth to offices and factories.

From the earliest days of the colony time was important. Convicts were sent here to do time, and their days were broken up into timed patterns. In 1797 Governor Hunter erected the first clock tower to the west of the settlement on what is now Church Hill. The tower was 46 metres high with its clock facing the town. The tower was damaged in a storm in 1799 and then collapsed in 1806. The clock itself was salvaged and re-erected in a smaller tower the following year.

The oldest clock still working in Sydney is in the façade of the Hyde Park Barracks. This was installed in 1819 by convict clockmaker James Oatley. Oatley, appointed as Keeper of the Town Clock by Governor Macquarie installed a number of public clocks across Sydney, with clocks in churches at Parramatta, Campbelltown, Windsor and Liverpool amongst others. The suburb Oatley is named after him.

Of the clock towers it is those at the Sydney Town Hall (1884), the Lands Department (c1890, clock 1938), the old General Post Office (1891), and Central Station (1921) that remain as the best examples. Each was built so as their clocks could be seen across the part of the city they stood in or from the approaching ferries to Circular Quay. Workers would check them as they went to their jobs. Their heights hint at the low scale of the nineteenth century metropolis and they could be seen across surrounding suburbs. Central Station, which was visible across the industrial suburbs of Redfern and South Sydney was colloquially known as “The Working Man’s Watch” for this reason. Town Hall Clock was visible from Balmain. Their prominence on the skyline was such that during World War II the GPO clock tower was dismantled for fear it would provide a target for Japanese air raids. It was not rebuilt until the 1960s.

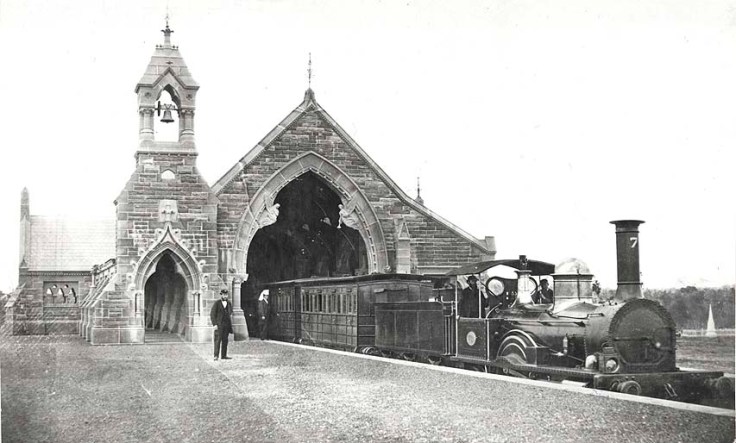

While the others worked independently, the clock at Central was the centre of an intricate system of integrated clocks around the station and across the Sydney train network. A system of electrical pulses regulated the time across the network so all showed the same time. Correct time is essential to safe and efficient running of railway networks and has been from the start. As such, the adoption of railway time as local time as the network extended across Sydney and NSW was instrumental in the eventual adoption of it as standard time for NSW and later Australia from 1895.

The scale of these clocks is not appreciated from the ground, but some ideas of the size of the mechanism can be taken from the fact that the Central Clock hands are 2.3m and 3m each, with the clock face itself is 4.8m in diameter. Upgraded in 2014 the Central Clock continues to provide accurate time, although fewer notice it these days.

Check out this short film on the history of the clocks on the Sydney system.