The ‘Thallium Enthusiasms’ were a spate of poisonings that occurred throughout suburban Sydney from the late 1940s through to the early 1950s, peaking in popularity by the middle of 1953. There were forty-six reported cases of thallium poisonings in Sydney between March 1952 and May 1953, ten of which ended in death.

By the close of 1953, six women in NSW had been charged with dosing family members with thallium. All of these women were put on trial for serving up food (such as scones, cakes or jam rolls) or drinks (usually tea or milo) laced with thallium to their relatives and loved ones.

William Crookes, a chemist, discovered thallium in the 1860s. Initially it used as a depilatory in dermatological procedures. Thallium induced hair loss, so its application was a way of eradicating scabies and other scalp conditions. It was also used to cure ringworm, although this use declined in popularity after the 1930s, when thirteen children treated with thallium died in Spain.

While thallium had these medicinal uses, its poisonous properties were soon realised and capitalised upon, and by the turn of the century, it was being sold as a poison for eradicating vermin. Both rural NSW and the inner-city suburbs of Sydney had a chronic rat problem in the twentieth century, with an estimated population of up to two million rats in inner Sydney by the late 1940s. Rats were carriers of disease, such as the bubonic plague or diphtheria, and were also a menace in family homes, having been found nibbling on the faces and feet of small children.

By the early 1940s, thallum was marketed in NSW as the rat killer ‘Thall-rat’. It was exempted under the Poisons Act of 1902 because it was such an effective rodenticide. Thall-rat was readily available at the front counters of corner shops, chemists and hardware stores across Sydney. Unlike other poisons, such as cyanide or arsenic, thallium was undetectable if served in food or drink: it was invisible, it didn’t smell and it had no taste. The main symptoms of thallium poisoning in humans were hair loss, gastroenteritis, numbness, blindness, loss of speech and eventually death.

Of the six accused thallium poisoners, the trials of three provoked a massive media frenzies. The first thallium murder trial was that of Yvonne Fletcher, of Newtown, in September 1952, who was charged with the murder of her first husband Desmond Butler in 1948 and her second husband Bertrand Fletcher in March 1952. The rat connection was strong, for her second husband was employed as a rat bait layer and it was from he that she obtained the poison.

Probably the most sensational cases of the day was that of 63-year old Caroline Grills, a serial killer housewife who is said to have attempted to poison eleven of her family members, succeeding in the murder of four. However, Grills was only charged with the attempted murder of her sister-in-law in May 1953. Grills’ trial, which was held at the Central Criminal Court from October 1953, attracted quite a lot of media attention. Throughout the trial, her somewhat unsettling demeanour was commented upon by the press, particularly they way she smiled, laughed and waved to the packed courthouse.

And finally, we have the case of Veronica Mabel Monty, who was accused of poisoning, but not murdering, her son-in-law, the popular Balmain Rugby League football player Bobby Lulham. Her trial, which began one month after the trial of Caroline Grill, caused scandal as it was revealed that Monty and Lulham had been conducting an affair. Understandably, it didn’t end well for all concerned, with two divorces and Lulham abandoning his football career. Happily for the people of NSW, the sensation of the Lulham poisoning forced the hand of the NSW Government to place restrictions on the sale of Thall-rat.

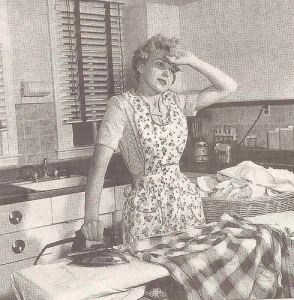

What made these poisonings unusual is that they were carried out by women within the seemingly innocuous setting of the home. Their offerings of food and drink were really murder attempts disguised as acts of generosity. None of these women offered compelling reasons for why they were set on murdering, or at the very least incapacitating, their family members. But it was the post-World War 2 period after all, a time when the freedoms that many women had won during the war, had been curtailed. Revenge or resentment perhaps? Or were these murderous rampages a reflection of the sublimated violence of the Cold War?

For more on the crimes of the wicked women of Sydney, check out the exhibtion Femme Fatale: the Female Criminal at the Police and Justice Museum at Circular Quay. It is open every weekend until April 2010. For further reading, Noel Sanders’ book ‘The Thallium Enthusiasms and other Australian Outrages’ is recommended.