A few weeks back, the so called fight of the century was fought out between Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao. It was a matchup between two who had avoided each other for as long as possible, are at the end of their careers and were paid more than just about any fighter in history.

In 1908 Sydney had its own fight of the century, between two fighters who had been trying to avoid each other and one who would be paid more than any fighter before him.

This was the world heavyweight bout between the American champion Tommy Burns and the black American fighter Jack Johnson.

But why Sydney?

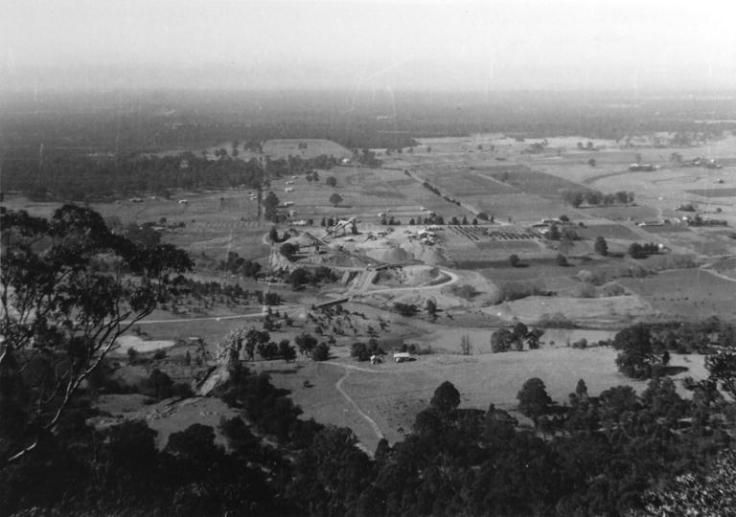

Burns was already in Sydney on the behest of promoter Hugh McIntosh, who had leased a site at Rushcutters Bay to build a temporary stadium for Burns to fight local champion Bill Squires, who he beat in 13 rounds. With about 40,000 locals turning out, McIntosh saw an opportunity to make lot more money by organising Johnson to come to Sydney as well.

Johnson was a tall, suave, Texan boxer, banned from fighting for championships in America because of his colour. Australia, with its White Australia Policy was equally racist, but not so much when it came to fighting. After much urging, and the promise of £6000, Burns agreed to fight if Johnson would come to Sydney.

The match up was confirmed for Boxing Day 1908 at Rushcutters Bay. Burns was touted as the Great White Hope against the savage Johnson, who had learnt to fight in six man brawls in Texas bars; last man standing was the winner. But Johnson was also a dazzling urbanite. He dressed in the best suits, had a gold tooth with a diamond in it and played the bull fiddle to relax. His training sessions became one of the hottest tickets in town.

McIntosh promoted the racist element of the match, commissioning Norman Lindsay to draw the fight poster with Johnson towering over an attacking Burns.

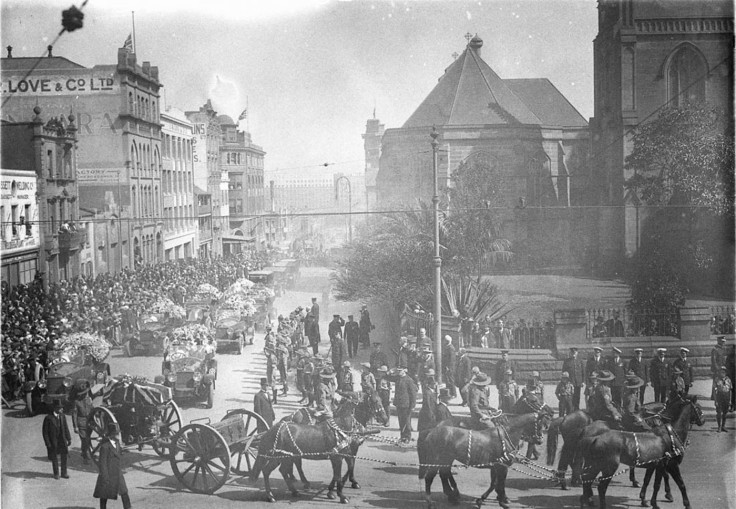

The day of the fight saw 20,000 people pour into the stadium and a further 25,000 outside. The Prime Minister J.C. Watson and Attorney General Billy Hughes both attended. Women were banned from the stadium, however a number dressed as men and snuck in regardless. It was said that Johnson refused to get into the ring unless his share of the purse fee was increased by £500, to £2000, an offer that McIntosh renegotiated with a pistol. In hindsight, with the gate takings equalling £26,000 he could have paid it.

The fight was filmed, one of the first sporting events in Australia to be recorded, and the stadium had phone lines set up so it could be reported. It was a terrible mismatch. Johnson savaged the world champion and was winning easily when police stepped in to the ring to stop the carnage. Johnson was crowned world champion, the first black boxer to win it. The fight basically finished Burns’career, but Johnson went on to hold the title until 1915 and continued to box until he was 50. Rumours abounded about his flamboyant lifestyle, which included his 4 marriages, an apparent drinking challenge with Rasputin, a time working as a matador and acting as a spy in WWI Spain.

Now that’s a fight worthy of a century.

Check Terry Smith, The Old Tin Shed for more